Interview with Carlotta Fortuna

Architect and texile designer

Design Department Director of Amini Brothers Company

“If I had to think about the originality of a carpet that hasn’t been designed yet, I would focus on craftsmanship; I would look closely at weavers, try to learn their secrets and, on this basis, I would try to invent new techniques. I would spend time studying history, along with the now-forgotten symbols forgotten; I would look for spirituality. Surely, striving for research, into new materials, looking at rejected samples will allow us to develop new aesthetic forms, new techniques, new types of language that we are still unaware of today…”

How did you start making drawings for Amini? Have you always been interested in stories and narratives dealing with carpets, or was it a revelation that came to you quite by chance some years ago?

Amini has been part of my career since 2016; at that time I was a textile designer of silk scarves in Como and trying to fulfil my ambition to express myself by drawing and painting as much as possible. I had struck a deal with my father: I would agree to complete my architecture degree and then I could finally enrol at the Fine Arts Academy. For a while, architecture completely blew me away. During my Erasmus studies, first at the École d’Architecture in Lyon and then at the University of Western Australia (UWA) in Perth, colleges with a far more artistic bent of mind than the Polytechnic, I made sure I followed as many landscape painting courses as I could. After completing my architecture studies, I was in no doubt that I would enrol at the Brera Academy of Fine Arts and that is just what I did. I switched from being in more or less stable full time jobs with reputable architecture firms, to working as a clerk in a furniture showroom in a job that allowed me to attend courses. Thanks to my work, I was able to travel a lot, and the experience I hold dearest in my heart was my time in New York, an exhilarating cultural reality.

One person and many roles inside Amini studio. In the work of the teams tasked with researching and developing colors and materials, and with fine-tuning the complex processing techniques employed in the various creations, there is more than a hint of Carlotta Fortuna. What would you say to be the strong points of the Amini collection?

We try to approach our work based on the wealth of different proposals. I mean, every job starts with different inputs and inspirations, they can come from all kinds of source, whether collaborations with other designers, or research work delving into historical archives, or even within the same collection of classic and vintage Amini carpets: a magical place we call the Vault, which can be visited at the company HQ. A great source of strength is the Amini family as a whole, who have built sound human relationships over the years that have enabled the brand to attract many different talented workers from all over the world.

“We try to approach our work based on the wealth of different proposals. I mean, every job starts with different inputs and inspirations(…).”

Given the complexity of the choices to be made, ranging from the conception to the realization of the finished product, how can drawings taken from a historical archive be turned into a successful commercial product?

Working on historical archives is always an exciting experience, for it whets your professional curiosity, but also makes you aware of your desire not to let people down. You enquire and delve deeper into the artist’s imagery, uncovering unseen or unpublished works; the historiographical research based upon the artist’s biography and the historical frame of reference help to internalize the artist’s work and trait. Each project follows different paths. It is hard to describe a process that can be regarded as the same for all the subjects made. Over the years we have had several collaborations, with Archives such as the Gio Ponti, Manlio Rho, or Ico Parisi institutes, with art galleries and ancient weaving mills such as Bevilacqua, in Venice, and each of these relationships has borne different stories. I think we have to yield a little of ourselves so that someone else’s work may shine through, to give back what the artist wanted to convey, to adhere to the nature of the original period of the design.

In these years you have produced hundreds of drawings. What is your ongoing source of inspiration? Is your investigation somehow the result of notes taken in your everyday life?

In my case inspiration is something that distracts me: it can come from anywhere at any time, regardless of what I am doing at that moment. It is as if we never stop making sketches, our mind continues to take snapshots of images and file them away in an archive, only to fetch them at the right time.

We live in a time when stylistic errors are a source of inspiration and of expressive originality, if you will. In the field of contemporary graphics, for example, a pixel, the basic unit of digital images, has become a fundamental ingredient for new abstract artworks.

Do you think that artistic error, in the sense of failing to comply with classical aesthetic canons, could be an element to work on in the future? How do you achieve originality in a segment that depends in part on craftsmanship and handmade crafts?

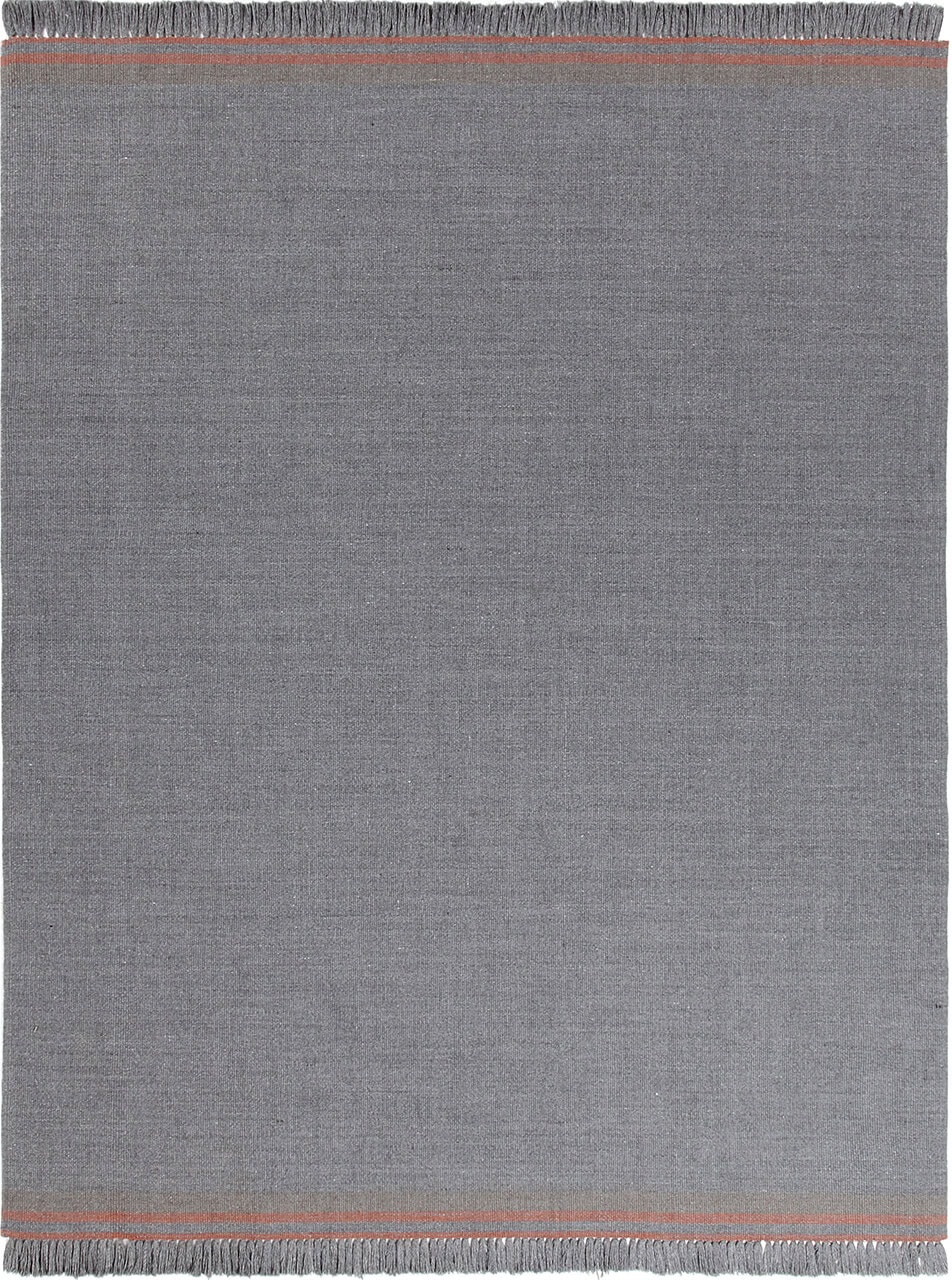

Errors are just some of the many tools that can lend originality to a product. Indeed, inspiration is often drawn from poorly executed samples, incorrect or incomplete renderings that allow us to set up new designs or achieve new effects. This was the case with the In/Lustro carpet, for example: during one of his trips to India, Ferid noticed an unfinished sample in which the unsewn edge was tipped with an unusual fringe. As a result of this “error” the idea was born to make a series of contemporary rugs, featuring a strong chromatic research, and that would overhaul the classic concept of fringe. This is why mistakes and errors are also stored for the future, so that one day they may provide new source images, new starting points, a new beginning.